An article by Ben C.

It’s 2016. I’m in my bedroom, stooped over my desk, eyes glued to my laptop screen. I’m playing online blackjack—and am up over $2000. In the next few hours, I go on to lose not only these profits but my entire student loan. Then, in a kind of acute distress only gamblers truly understand, I stalk the empty streets, bawling on the phone to my mother, begging her to bail me out.

With any serious addiction, there is a ripple effect. In most cases, those who use substances or engage in addictive behaviours aren’t just hurting themselves, but also the people around them.

However, gambling is somewhat unique in the respect that it comes with immediate material repercussions. Certainly, those with a substance use disorder may lie, cheat, or steal in an attempt to acquire more of the drug or to keep their addiction secret, but only gamblers can make their family destitute in a single night.

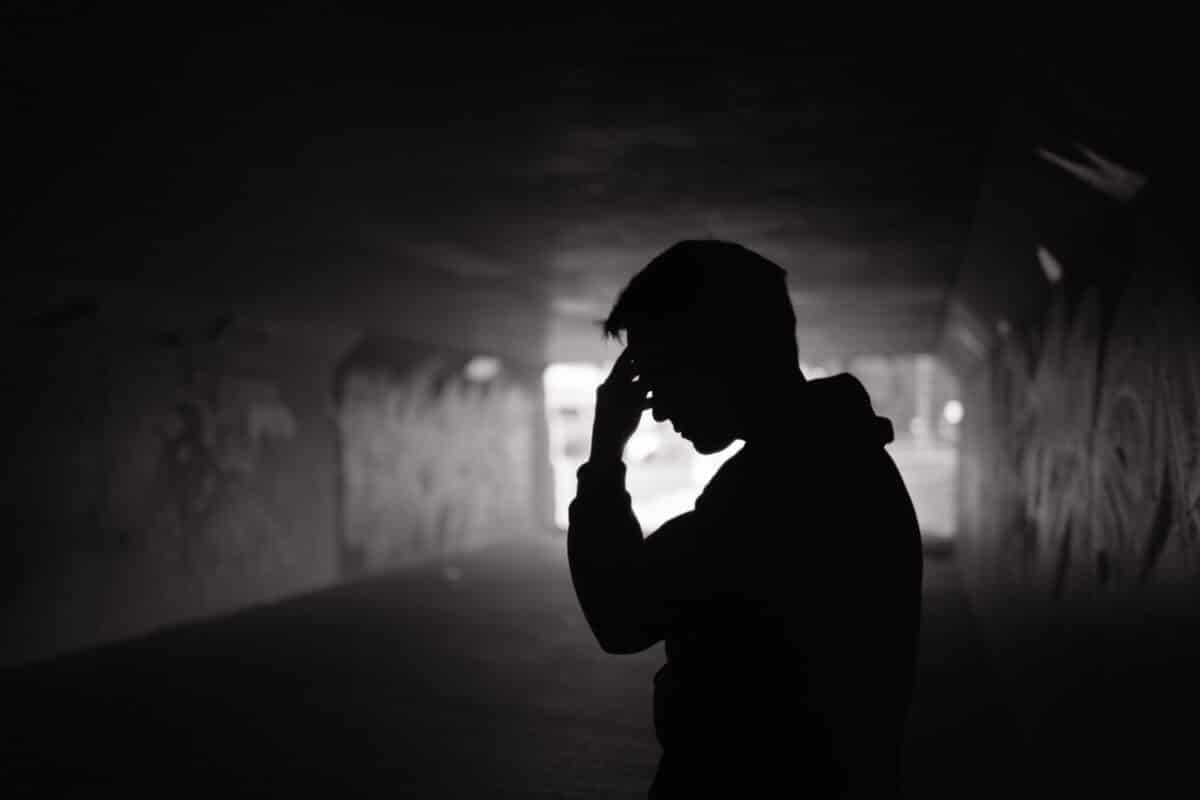

The mix of guilt, shame, and despair we gamblers feel is of a type unknown to most. What’s worse, given its ostensibly selfish quality—one suggestive of a complete lack of concern for loved ones—compassion doesn’t come easily to those affected by our addiction.

Myriad factors contributed to my gambling addiction and, given the complexity of the issue, it’s impossible to have anything more than a rough understanding. That being said, I have little doubt my mental illness played a major part. Sometimes, despite our better judgement, no matter how many times we break our promises, we are slow to confront the realisation: when it comes to a gambling addiction, the house always wins.

The illusion of control

My first real experience of gambling occurred when I was sixteen. I used my mother’s debit card to make an account on an online poker site. It wasn’t long before I’d lost $100 and had my first taste of gambler’s defeat: that combination of shame, despair, and deceitfulness that would become a hallmark of my adult life.

Confined to her bed, suffering from depression and PTSD, my mother was none the wiser. The lack of guidance and discipline I received in my adolescence meant I would have to learn self-control the hard way.

As the years progressed, I went on to form a longstanding addiction to online poker. Compared to the antics of my late twenties, it wasn’t anything too high stakes. I was able to stop before draining my bank account, still labouring under the illusion of control.

At twenty-one, I experienced a drug-induced psychotic episode. A deadly mixture of genetics, trauma, and high-strength cannabis were the likely culprit. After getting professional help, I was prescribed an antipsychotic called amisulpride.

Thanks to the support of my friends and care team, I was eventually housed in a council bedsit. Shortly after, my brother came to live with me and slept on my sofa. Despite the fact I was aware of its deleterious effect on me, I continued smoking high-strength cannabis and playing online poker—lots of online poker.

While I knew this gambling was certainly detrimental and irresponsible, my internal failsafe prevented me from blowing all my funds. It wasn’t until many years later, when I experienced my second, much more terrifying episode, that this weak mechanism finally broke.

Chasing the rush

The best way I can describe gambling is that you’re completely removed from yourself. Every fibre of your being is focused on the fall of the cards or the roll of the dice. Completely suffused with adrenaline and feel-good chemicals, you teeter on an intoxicating threshold. No matter how ostensibly “good” a win makes you feel, nor for that matter, what your rational mind tells you, it’s actually that in-between state you’re chasing.

This “rush” isn’t positive or negative and doesn’t fit into such a binary. I would describe it, perhaps counterintuitively, as a feeling of aliveness, like flying in a dream or a last-minute stay of execution. Of course, on my many benders, I knew all this, but didn’t spend much time analysing it—that would mean actually confronting my addiction.

Hooked to that deadly buzz, my very cells fizzled with every sporadic win. But it isn’t just winning that gets us high. Research shows that, even when gamblers are losing, their bodies still produce adrenaline and endorphins. I would go so far as to say it was less winning, but losing that heightened my high, magnifying the rush that was bound to come, any…moment…now.

Video slots, poker, blackjack, roulette, sports betting—I’ve done it all. Gambling was normalised within one of my social groups, and we all essentially enabled each other. But it was my solo gambling binges, subsequent to my second psychotic episode, that were the most extreme.

The severity of this event precipitated a proportionately severe gambling addiction. I’m not entirely sure why, but I put it down to the fact I’d never been more desperate to escape from my symptoms. I needed bigger and bigger rushes to feel, for lack of a better word, “normal”.

Irony of ironies, my brother is a successful professional poker player and, along with my mother, bailed me out numerous times. I realise how lucky I was to have this financial support. Many people with such an addiction end up ostracised and homeless. However, as my brother once pointed out, my awareness of this safety net may have kept me from fully appreciating the consequences of my actions. Sometimes, even though it’s awful to experience, rock bottom can facilitate the greatest change.

The science of gambling

Think of the reward system in your brain like the gas pedal in your car. It gives you the go signal to move toward what you want. Conversely, the top-down control network (the prefrontal cortex) tells you to slow down or stop what you’re doing. When the brain is in a state of homeostasis, these two sections work in harmony to foster a sense of wellbeing and self-control.

Addiction is like a communication problem between the gas and brake pedals. As you continue to engage in the habit, you keep pressing the gas. However, when it’s time to stop, the breaks no longer work. By the time you realise gambling has become a habit, your brain activity shifts away from conscious control. It can feel like you’re on autopilot. Once the habit has taken over you become extremely susceptible to gambling cues and triggers. Even though it’s no longer fun, you continue to do it to escape the negative impacts of these triggers.

As the consequences of your gambling get worse, so does your mood. At first, the addiction appears to make you feel better, but the more frequently you gamble, the lower your natural mood setpoint drops. This feeds into your daily life even when you aren’t gambling. Not only can this addiction exacerbate existing conditions, but it can also cause mental health problems, like depression, low self-esteem, or anxiety.

We’re here to help

Let’s talk

Call now for a totally confidential, no-obligation conversation with one of our professionals.

How schizophrenia contributed to my gambling addiction

There is a lack of research on the relationship between gambling and psychosis. However, as this study shows, a high percentage of those with disordered gambling meet the criteria for another co-occurring disorder. Moreover, research from 2009 suggests that up to one in five individuals with schizophrenia may experience problems related to gambling.

So why is this?

It may seem counterintuitive that someone with schizophrenia would develop a severe gambling addiction. At a glance, the connection seems tenuous at best. However, when we take into account the so-called negative symptoms of the condition, the relationship begins to make more sense.

Most people are familiar with what are termed “positive symptoms” of schizophrenia (delusions, hallucinations, disorganised thinking, etc.). “Negative symptoms”, on the other hand, refer to the absence or reduction of normal emotional and behavioural functions. These can include affective flattening (reduction in the range and intensity of emotional expressions), avolition (decrease in motivation and goal-directed behaviour), and anhedonia (reduced ability to experience pleasure or interest in previously enjoyable activities).

Based on my experience, it’s tricky to separate the negative symptoms of my mental illness from the side effects of my medication. This is echoed by research, as this study points out:

“Antipsychotic drugs are thought to produce secondary negative symptoms, which can also exacerbate primary negative symptoms.”

Given that most antipsychotics block dopamine receptors in the brain, and dopamine is the neurochemical chiefly associated with pleasure and motivation, it’s easy to see how they could contribute to negative symptoms. Gambling, given it utterly consumed my focus, not only offered an escape from my delusions, but also caused a chemical rush that provided relief from my negative symptoms.

The road to recovery

I’d love to tell you that, after meeting my wife six years ago and finally quitting drugs, I never gambled again. Unfortunately, this addiction has been the hardest for me to shake. I became what is known as a binge gambler. This is someone who doesn’t gamble regularly and can abstain for long periods, but when they do indulge it’s usually to an extreme.

While I’ve never sunk to the depths of former years—getting into enormous debt and wasting thousands of dollars—I’ve been susceptible to sporadic bursts. These incidents have put a huge strain on my relationship, not only because they compromised our financial stability, but because I always lied about my addiction. The foundation of love is trust. When you breach that trust over and over again, your gambling isn’t just self-destructive; it’s extremely hurtful to those who rely on you.

The last time I gambled was in the summer of the previous year. My wife and I had a big argument and, feeling low, I gave into an urge and blew a couple of hundred playing poker. Though this doesn’t seem like a lot, when you factor in my track record and propensity to lie, it was close to the final straw.

That was when I made the last of many final commitments. Never again would I engage in any kind of gambling, no matter how seemingly insignificant. Now, if I’m triggered, I don’t let it take root or fester, but open up about it to my wife.

It’s been many months since I’ve had urges, and what little ones I have experienced were easy to quash. This is partly because I’ve been regularly engaging in mindfulness practices, and also due to my newfound purpose. Before, I was unemployed, single, and very unwell. Now, I am well on the road to recovery, with a blossoming career and a family to support. I’m not going to let anything jeopardise that again.

My advice to those struggling with a gambling addiction is to do what I should have done: seek support. Gambling is highly stigmatised and often isn’t viewed within a pathological context (think “degenerate gambler”). However, while you are accountable for your actions, you are also worthy of receiving love and care.

Don’t suffer in silence. Communicate with friends and family, join a Gamblers Anonymous support group, or reach out to White River Manor. Their world-class team has a wealth of experience in treating all kinds of addiction and mental health disorders, and programs that they will tailor to meet your specific needs.

To see how they can help, contact them here for a confidential, no-obligation conversation with one of their mental health professionals.